“Clear!” Shocking Medicine in Games, Literature, Film, and TV

Aside from being a writer and game designer, my secret identity is as a critical care nurse. I’ve been wanting to write this post for the past couple of years, but a couple of TV shows this week caused me to pulled the trigger. Arrow is the first episode I’ve seen on TV where they ran a Cardiac Code even close to what I would expect. Unfortunately, the previous week’s Flash had its entire storyline revolve around bringing people back from the dead like Frankenstein.

It’s a familiar scene: a key character in the show you’re watching is on the operating table and their heart stops beating (ie: they “flatline”). Maybe the doctor yells for a medication. If the character is lucky, someone starts doing chest compressions. But 99.9% of the time, before anything else is done, the doctor will grab a pair of paddles and yell “CLEAR!” before sending a jolt of electricity through the patient that causes them to jump off the table. Sometimes the heartbeat will come back. Sometimes they’ll shock them one more time, unsuccessfully, then give up and call the time-of-death.

Dramatic? Sure. Effective medicine? Absolutely not.

Shocking a flatline in a patient is one of the things in popular culture that drives every medical professional out of their mind. It is so pervasive that most people on the street would agree that the most effective way to restart someone’s heart is to grab whatever electricity-generating device is nearby and throw volts through their chest.

Without taking anything else away from this post, I’ll break it down for you:

Never, ever, for any reason, have your “medical professional” shock a flatline.

Why not shock a flatline?

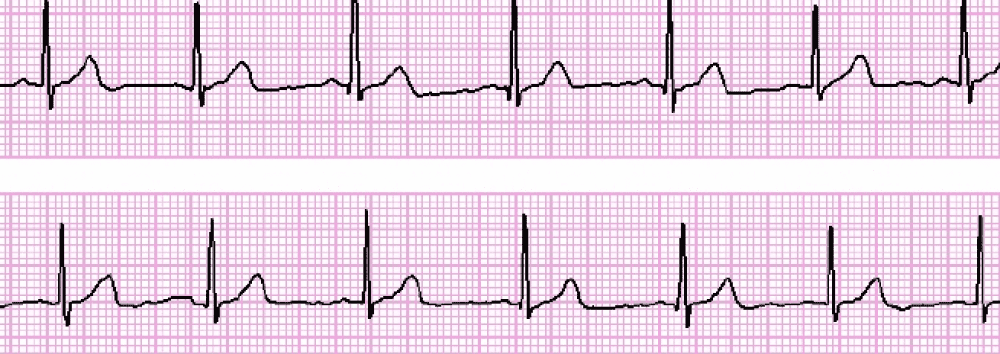

Fibrillation (Ventricular Fibrillation or V-Fib), is a fancy word that means “quivering”. The heart doesn’t beat, it shakes. That means there is electrical activity going through the heart, it’s simply a disorganized scramble of information that’s preventing the heart from moving blood around the body. When you de-fibrillate someone, either with a hospital defibrillator or the kind of Automated External Defibrillator (AED) you find in an airport, you send a shock through the heart that, in a way, reminds the heart’s confused electrical activity where it’s supposed to go. Without any electrical activity in the heart (as in a “flatline”) you might as well be shocking a piece of steak and expecting it to stand up.

What is involved in a real Code Blue?

All codes vary depending on circumstances–Were they a witnessed arrest or found unconscious? Were they in an ICU? General hospital ward? Home? In the car? Having said that, there are a few ground rules that form the foundation of all cardiac or respiratory arrests.

- “Get on the chest”, ie: start chest compressions.

- In Hospital/EMT: Get an airway established (called intubation)

- In Hospital/EMT: Give drugs, such as epinephrine, vasopressin, or atropine.

- Do not stop compressions for anything short of giving a breath (and only if you are totally alone), or shocking the patient with an AED (Automated Defibrillation Device, like those at airports) or professional defibrillator. Do Not Stop Compressions. [Note: Almost no one uses paddles anymore. We place pads on the chest as soon as possible, which grants us far more flexibility and information.]

- Do compressions for 2 minutes before checking the heart’s rhythm and shocking IF NECESSARY. I will repeat: Never, ever, for any reason, have your “medical professional” shock a flatline.

- Get back on the chest and repeat with #1.

So what do we normally see in Pop Culture and what is it supposed to be like? Let’s look at a few of the most common situations.

Character collapses in public

It’s far more common for characters in TV shows or movies to clutch their chest walking down the street or sitting in a restaurant. When that happens, you should check to see if the person is responsive and if there is something obvious happening, like they have a blocked airway. If not, the first thing you need to do is “get on the chest” (ie: start chest compressions, about 100 per minute or more for adults, but the speed is not as important as letting the chest recoil fully. That’s the only way blood feeds the heart’s arteries).

Should you check for a pulse first? You can, but doing chest compressions on a heart that is still beating will not cause an issue and quick reaction can save a life.

If the person has no pulse and was talking and walking previous to the attack, the most important thing you can do is get the blood circulating, not putting more air into their lungs. If they were talking, they were breathing. We only use a fraction of the oxygen we inhale, so that means there is already plenty of oxygen in their lungs. Having said that, you should give “rescue breaths” as you’ve been taught in your CPR class.

DO NOT stop compressions until a professional arrives and tells you to stop or if you’re alone and must give rescue breaths. If you get tired, have someone else take over. Professionals won’t stop CPR unless the heart starts working on its own. Think of chest compressions like pumping up a tire with a slow leak. The more you pump the heart, the higher the patient’s blood pressure goes and, in general, that’s a good thing. Without a beating heart, BP is 0/0, and that means dead.

When professionals show up, they will put defibrillator pads on the patient and place a breathing tube (called an endotracheal, or ET tube) into their airway (called “intubation”) to either “bag them” with an ambulation (ambu) bag or connect the tube to a ventilator. This is to control the oxygen the patient is getting, but is also used to “protect the airway”. When someone is unconscious, they cannot control their swallowing reflex. Even if they don’t vomit from pain, trauma or overdose, saliva in their mouth will leak into the lungs planting the seeds for severe pneumonia down the line. The professionals will continue the compressions and start drugs (see #2) while they transport them to a hospital.

The defib pads and EKG leads will help them read the rhythm of the patients heart to find out if they have a “shockable rhythm” (Hint: flatlines are not shockable rhythms). If they are in Ventricular Fibrillation (V-Fib), then they will attempt to us the DeFibrillator to shock them back to a normal heart beat.

Character is “found down”

Trigger Warning: The medicine and human emotion in "The Body" is excellent, but still gets me a over a decade later.

It’s far less common to find a character on the ground in popular culture, though some of the most impressive scenes in TV are based on it. When that happens, you should do all the things above except you could give some “rescue breaths” in order to get fresh oxygen into the lungs since you don’t know how long they’ve been down. When you do chest compressions, the lungs will get some oxygen moving through them even without breaths (unless their airway is blocked), but you do want to make sure that some fresh air is getting in there.

Flatlining in a Hospital or Operating Room

Professionals will “Call a Code” immediately, meaning a page goes out to a specific team of individuals designated as the Code Team for that shift. Ideally, a Code Team consists of a pharmacist, either a Fellow or an Attending (though Residents are common on nightshifts), a code nurse (typically a highly experienced and specially trained ICU nurse) and possibly the hospital supervisor. It’s also common for two dozen people who don’t really need to be there to show up, but I won’t get started on that so back to the Code.

While professionals call the Code, someone will immediately “get on the chest” and start compressions. If the patient is supposed to be at an advanced center of medicine, the professionals will start giving drugs as well; epinephrine, vasopressin, and atropine are common.

The character will then be intubated and have pads placed (if they weren’t already) and the rhythms will be checked periodically to see if they are shockable. Meds will continue to be given every 3-5 minutes, compressions will not stop, and central lines will be placed. This will continue until the patient’s heart starts beating again on its own, or the MD running the Code calls it (can be from 20-60 minutes depending on what’s happening with the patient/character).

A Few Notes

Giving Wake-Up Juice

As a side note, if your character is unconscious, they will not be able to protect their airway, so do not give them fluids or medications (or a “Miracle Pill” for that matter) by mouth. You can give them medications that dissolve in the mouth, intravenous (IV) injections, transdermal patches, hyposprays, or whatever non-oral route you choose depending on your story’s tech level.

Endotracheal (ET) Tubes

When your patient is unconscious and intubated, the tube will not stay in the airway without being secured in some way. Tape, gauze strips, or devices specifically designed to secure tubes are all fine. I’ve seen far too many tubes dangling out of the closed mouths of patients, I assume because the actor is clamping their teeth on it. Your unconscious patient won’t be so obliging.

Examples

Robocop

Only one movie I know of got it close to right, the 1987 cult-classic, Robocop. In the scene after Alex is shot and is on the hospital table, his heart goes into V-Fib. The doc calls for a defibrillator (de = removal; fibrillation = shaking), they shock him to attempt to ‘reboot’ the heart’s wacky electrical activity. They also give him drugs. It doesn’t work and they do it again. Eventually he flatlines and they call it. It’s a fast scene. It’s a dramatic scene. Yes, a real Code Blue would go longer, but it works in this case because they aren’t really that interested in saving him; they want his body for experimentation.

Arrow

Season 3, Episode 20: “The Fallen”

Ollie finds Thea stabbed through the gut with a fairly large sword. Ignoring the fact that she should have been dead within minutes, they did several things right in this episode, at least once they got to the hospital.

While she was on the table, she went into what kind of looked like V-Fib. It didn’t look perfect, but at least it wasn’t a flatline, or even a normal rhythm (see Winter Soldier below). They gave her epinephrine and immediately grabbed some paddles. No one yelled “she flatlined”, which is great. Also, no one yelled “she’s in VFib” (see Winter Soldier below), but that’s okay. They shocked her and it didn’t work. The key thing here is that she then flatlined and the doctor told someone to get on the chest and start compressions. Now, ignoring the fact that compressions should have happened immediately, the key thing to take away here is that the doctor DID NOT repeat the shock! It was the CPR that brought her back, which is solid. Hospital resuscitation techniques, which includes drugs, has a far better success rate than bystander CPR (bystander CPR is critical, btw. No matter what percentages you hear about the success rates of bystander CPR, do it. I have personally worked with patients whose lives were saved with total recovery because someone in the field did excellent CPR until they reached our CCU).

I was so happy to see this scene that I did a little dance.

Unfortunately, I’m a bigger fan of The Flash and they had an entire episode rubbing their crazy medicine in my face.

The Flash

Season 1, Episode 18, “All Star Teamup”

I love the Flash. It’s a fun, interesting series that draws on some of the best storylines and characters from the comics. Which makes this episode all the more disappointing.

In short, a supervillain is killing people with robotic bees (yeah, not their best subplot). The people go into cardiac arrest almost immediately after being poisoned and flatline. When Barry gets stung, the same thing happens. “Luckily” Cisco built a defibrillator into the suit (I’m going to say that its significant battery power gets regularly charged by Barry’s movement, because otherwise I have no idea where this battery is supposed to be.) Unfortunately, Cisco decides that shocking a flatline is a good idea. Will it make it worse? Well, no, Barry’s already dead. As in dead, dead. The extra frustrating part is that Caitlin is supposed to be a biologist with near-MD levels of medical knowledge. She should know better so her credibility goes out the window.

Later in the episode, Cisco is stung and Barry generates an electrical field with his speed powers to restart his heart. The ONLY way I will accept this is if someone later retcons it to mean that Barry actually infused Cisco’s heart with some trickle of the Speed Force that caused it to start moving on its own, which would be fine. Otherwise, this is total crap and pulls the rug out of my desire to suspend my disbelief that anyone at S.T.A.R. knows what they’re talking about when it comes to medicine or biology.

Captain America: The Winter Soldier

Winter Soldier, one of if not the best of the Marvel films, also fell through this hole.

Nick Fury gets shot and is on an operating table when alarms start going off. They call out that he’s in V-Tach and yells for the defibrillator. Now V-Tach is not V-Fib, but unstable V-Tach can be “converted” using a shock. This is not the same as shocking someone out of V-Fib.

On the monitor, Nick’s HR was around 120 (which is actually normal when you’ve lost a lot of blood), and it looked like a normal (sinus) rhythm, albeit Sinus Tach (meaning a normal looking rhythm but faster than 100 beats per minute). This is pretty common for TV shows and films because they only seem to have one type of rhythm programmed into their “Ping” machines, but the Arrow episode above actually showed what could be considered V-Fib, so WS loses points to a TV show.

They shock Nick and he flatlines. Since his HR, according to the monitor, was actually Sinus Tach and not something anyone in their right mind would shock, they probably shocked “R-on-T” and killed him. They then gave him a shot of epinephrine, but since he had no heartbeat and no one was doing compressions, no blood was circulating through his body, meaning that the epi would just sit in the vein not doing anything. Since the epi didn’t help (to no professional’s surprise) they shocked his flatline, because the top-end SHIELD MDs got their medical degrees from watching Grey’s Anatomy and ER and think a heart works like a car battery. They then called him dead after about 1 minute of not trying very hard.

In the end, this was a pretty standard movie Code. I give +10 points for at least trying to shock him before he flatlined, but they lose 100 for shocking a normal, healthy rhythm for a guy in hypovolemic shock and killing him.

A few other things are important to mention here.

- A dead body looks WAY different than a living one and both Cap and Widow would have been able to tell he wasn’t dead immediately.

- Also, slowing your heart rate to 1 beat a minute still kills you whether you do it on purpose (with dendrotetotoxinite or whatever they babbled) or your heart stops on its own.

Whether you’re a prose writer or running a game, knowing a little bit about how emergency and ICU medicine works can provide a verisimilitude that allows your readers, watchers, or players feel the actual drama and stress that can happen in a Code and help give them a foundation of belief in your characters or NPCs.

Edited for spelling errors, to add images, and to include a cut section on characters being "found down".