Crazyhead, Misfits, and Glorious Incompetence

This article includes mild spoilers for the TV shows Crazyhead and Misfits. It’s not crucial information, but I always like to give a warning.

One of the core principles of classic tabletop games is that people want to feel cool and do awesome things. This might mean becoming a powerful wizard that battles for control of the cosmos. It might mean becoming a knight that serves a liege lord and being the go-to troubleshooter for the kingdom. It might mean you are the baddest bike messenger in town, and your cybernetically enhanced muscles are here to prove it. Heck, it might mean you are the best heel in all of World-Wide Wrestling. Rarely does the player or group set out to say, “Our goal is to be utterly awful at what we are doing.” Fiasco and Paranoia do a twist on this – Fiasco is basically a Coen Brothers film, and Paranoia extols the inanity of bureaucracy – but in a classic sense, this is still rare. However, let us not forget the immortal words of Doc Hammer, one of the creators/writers of The Venture Bros., “This is a show about failure. Glorious, wonderful failure.” Everyone wants to be awesome, but let’s consider – if even for just a moment – that being awesome at failing might be something to try out.

It’s easy to say that any game with a success/failure mechanic has failure as part of storytelling, which is true to a certain extent. Any DM worth her salt is going to take a failed roll and make something cool out of it. This is particularly true in the case of a contested skill test. The comedy/panic of a character failing to intimidate or seduce their target often writes itself. Despite this, I wouldn’t say D&D 5e expects the characters to fail consistently. The chance of failure needs to be there, though, or else why have the roll at all? What if 5e did expect characters to fail consistently? What if the players were lazy, self-centered, and generally unambitious? What if the defining characteristic of the adventuring team is that they were amazing at making situations worse? Well, that would look like the stories told in Crazyhead and Misfits.

Both of these shows were written by Howard Overman, though Misfits occasionally had different writers as the series went on. Interestingly, the first season of Misfits was also directed by just one person. Crazyhead has only seen two directors. This is a little beside the point, but this kind of consistency is huge for storytelling. Anyway. The theme of each of these shows is the same – people get powers, but they largely use them selfishly and without any thought as to consequences. Society looks down on the main characters for their behavior or actions – criminal behavior in the case of Misfits and mental illness in the case of Crazyhead. In each case, the protagonists attempt to use their powers for good, but are still the selfish, not-very-motivated, largely clueless heroes. They still try to do good, but in the easiest, least-planned way possible.

For example, in Crazyhead, Amy and Raquel discover that Amy’s roommate, Suzanne, is possessed by a demon. They kidnap her and drive her to an abandoned warehouse in order to perform an exorcism. Raquel tells Amy she is confident she knows all of this stuff, and they will get her friend back. They drive to this location with Suzanne thumping and screaming – though muffled – in the trunk. When they reach the warehouse, Raquel breaks out her phone and Googles “how to perform an exorcism.” She swears this is because she knows how to find the real stuff, and that Amy shouldn’t worry about it. Of course, this scene goes slowly downhill, first because it has Amy do stuff like urinate and bleed all over Suzanne, and then because the exorcism is working, but obviously going sideways. The ritual ends with Suzanne not only dead, after Raquel said it wouldn’t harm her, but coming back as a revenant. Whoops! While this is undoubtedly humorous, and this sort of bad decision making propels the narrative, it’s not indicative of people who are good at this sort of thing.

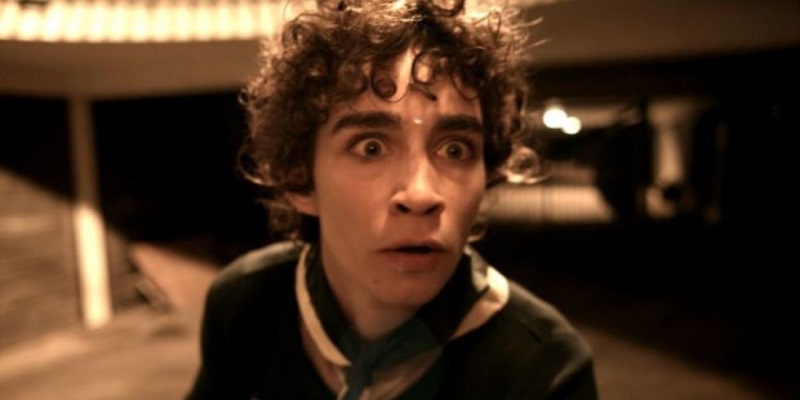

Another great example is Nathan in Misfits. Nathan is a brash, annoying kid who never believes himself to be at fault for anything. He firmly believes he is arrested and sentenced to community service because he just ate some pick and mix at a bowling alley without paying for it. Nevermind the fact he practically destroyed the place as he was running from the proprietor. Nevermind the fact he stapled the manager’s hand. Once all of his other community service compatriots get super powers, he spends the entire time doing stupid shit trying to figure his out. When he eventually ends up with the power to manipulate reality, he decides to go to Las Vegas to become rich. He performs at a magic show, and then proceeds to play craps and win big. This is all well and good until he forces the dice to show a 7 and a 4 in order to hit the total of 11. He’s an idiot and doesn’t think through the consequences. Even with tremendous power, he results to petty, criminal behavior.

Even when the protagonists in each show try to do the right thing, they do so in an awkward, off-putting manner that is very true-to-life about how most people would react in a similar situation. Attempting to do the right thing often results in making things much worse, such as hiding your revenant friend in the woods until you can eventually Google a cure for her, or hiding the body of your parole officer because he became a hulking monster and tried to kill you. These are completely reasonable solutions for these characters at that point in time. They are so inept at their newfound life, their bad choices are the only ones they are qualified to make. They fully live within the moments of the poor decisions. The immediacy of their ignorance is a thing of glory. Why? The world responds to their ineptitude with a mixed bag of failure and success. If it never worked, the character’s behaviors would need to change. If it works sometimes, well, it worked that one time, so don’t knock it!

This push/pull relationship is critical to making this work. Constantly failing isn’t fun, no matter how zany and wacky it might be. Constantly winning can be fun for a certain percentage of people, but I think most people would agree that being challenged, failing, and trying again to succeed is much more satisfying. This is typically expressed with characters being extremely competent within their purview, squaring off against equal or superior foes, overcoming the odds, and foiling the plans of the opposition. I’m not talking about a “defeating the villain/saving the world” specific structure, here. This framework fits over all kinds of narratives – domain management, micro-level agriculture, playing as bad guys to take over illegal businesses, and so on. This is a typical narrative structure for a reason: it’s highly successful and easily engenders engagement. The above shows take this framework and flip it on its head. The characters have power, but lack competence. The main source of their failure is themselves, and foes they encounter should be easily overcome, but they prove challenging. Most of the time the characters are so self-centered they lack any awareness of the antagonist’s plans at all. This inversion completely changes the narrative, as it should.

For players, this might be hard to swallow. Not succeeding at something when you are trying to show how awesome you are sucks. It sucks so much that a lot of DMs have shifted the narrative action portion of combat and skills to occur after the roll resolves the outcome. That’s a style that can be hard to get used to, but one that at least supports the players really describing what they are doing without having it all go to waste. In a game built off of character success, that’s a crucial piece of the puzzle. If your game is instead built on character failure, the first method is a necessity. Players need that immediacy of diving headlong into a situation without knowing the outcome. Everything needs the opportunity to blow up in their face. The more impactful the failure, the better. By impactful, I mean that it needs to interact with the narrative in a way that is visible and sensical. I don’t mean just punishing the player. If they try something and fail, resulting in death is fine every now and then – and only if the situation truly calls for it. (“You said WHAT to the Empress?!”) Instead, this is about their decisions really having narrative weight.

There doesn’t need to be a system in place for this, just a shift in narration. Other games have success or failures by degrees, or a system that makes every outcome a success and a failure, to a certain degree. Those are certainly options, but they don’t need to be the case here. Instead, you can reach this point by simple narration and formation of situations. Remember, the protagonists in those shows have more power than most others in their world. They just wield it badly. The characters rarely, if ever, get into a straightforward conflict. Putting the characters in situations where they can’t help but succeed isn’t the right answer for this type of campaign. Instead, everything should look like a nail to the player’s hammer. The situation might or might not be a nail, in fact, it’s probably a hex bolt or machine screw more often than it is a nail, but every so often it IS a nail. This, of course, does require a lot of buy-in from the players, but no more so than anything else does. Convincing people to play the Venture Brothers, Nathan, or Amy isn’t a hard sell, really. There is comedy to be had in these situations, and it makes the moments of drama and action all the better as a result.

When you are starting up your next game, introducing a new leg of a campaign, or simply trying out a new adventure, why not ask your players if they are up for something different? More often than not, something like this can help players stretch and grow. After all, no one tells stories about that time they encountered some bandits and dispatched them with appropriate efficiency. They tell stories about the time they accidentally knocked the Duke of Westchester unconscious because they thought he was a burglar thanks to the divination that the wizard performed earlier that day. I am not saying this is for everyone, or that it should necessarily be a full campaign, but spicing up a normal group with this type of storytelling? Yeah, that will be a war story. What more could you ask for?