Kilodungeons and Campaigns

I admit that I’ve never been all that familiar with megadungeons. I am not opposed to the concept, but most campaigns I have played in are either dense political sagas – walking and talking is paramount – or are told in a more epic style – Gilgamesh, not dank purps. Thus, most of my megadungeon exposure has been in reading the experience of others, seeing play third hand, and just doing my own historical digging. There is a large divide online about the how the purpose of the megadungeon must be portrayed. One faction seems to say that in order for it to be a “true megadungeon” it must have existed for time immemorial, have an established mythos without a clear truth, and have its own varied ecologies throughout. The other primary faction says the megadungeon should exist with clear intent, and the mythology and purpose should be integrated with the contents. To me, this is an individual campaign difference rather than a type of campaign difference. Regardless, one of the points agreed on is that the dungeon itself can serve as the entire focus of the campaign. I say “can” as an exploration game might have a megadungeon within it, but the exploration might occur in myriad areas, the dungeon might just be a side area the PCs can visit whenever they feel like, or other, various implementations. Thinking about – though never experiencing – megadungeons put me in mind of something that is common place in other game mediums: the kilodungeon.

What is a Plethora Kilodungeon?

As the name implies, the kilodungeon is larger than a standard dungeon, but not quite the world-spanning scale of the megadungeon. What establishes it as a unique entity unto itself is the presentation of the kilodungeon as a contained environment with a set story told throughout it and a generally striated structure – not unlike a walled city. The dungeon is specifically structured in a way to tell a complete story with multiple, smaller stories feeding into the larger story along the way. Kilodungeons can be a significant part of your leveling experience. It is not an uncommon experience for a kilodungeon to fill a full tier of play. This can span from starting play to mid-level, mid-level to high-level, top end, heroic to paragon – whatever. Players are also not ever locked to completing or exploring the dungeon once they enter into it. Leaving and returning is fine, and if the players don’t want to deal with the dungeon then the dungeon continues to do its thing. If you take this to mean that kilodungeons don’t necessarily need to be world-spanning threats, you are absolutely correct. The scale can be as grand as you want to make it, though it should have some impact that is felt in the outside world. Taken in this context the entirety of the Temple of Elemental Evil is a good example from D&D – particularly when read from Princes of the Apocalypse, though this presents more of a cohesive campaign centered around the kilodungeon than solely the kilodungeon itself.

This sort of implementation is incredibly common in older MMOs. The focus of those games was more of an ambient story – implied experienced interspersed with some sporadic questing. These games are now derided as overly grind-centric – modern games just shy away from xp-grinds and replace those with different grinds, but I digress – and this was in large part thanks to these kilodungeon experiences. A player would spend countless hours around a specific “camp” of creatures – generally 1-10 – killing them over and over again. This was more a indictment of the number of players in an area at a given time rather than an indictment of the system itself. If only six people are in a dungeon, your camp is now as far as you can progress and move instead of worrying about adhering to a certain area to avoid a fight with other players (in a tabletop game, tension with other groups trying to horn in on your claim is just good fun – provided your group is on board with that, of course.) If you step back from that, these dungeons that span across a variety of level ranges and prevent a complete story are pretty interesting ways to provide story and play experience.

Portal – A Kilodungeon Game

In a lot of ways, the video game series Portal fits the definition of a kilodungeon to a T. You are sent through a series of puzzles and encounters that relate entirely to the “dungeon” itself while providing you the story – or at least heavy story elements – through ambient storytelling. The tension exists through the central conceit of the story itself – what is the truth of what you are being told vs. the truth of what you are experiencing. The entire “dungeon” exists to explore that story and help you draw your own conclusion on the matter. The graffiti, voice recordings, destroy objects, conspicuous object placement, and the layout itself that tells of a specific path to a specific goal – though the question lingers whether or not this is your own choice or not. In the case of Portal, the kilodungeon isn’t a megadungeon – even though it provides us the entire known world – because it doesn’t meet the agreed-upon requirements set forth by the most vocal megadungeon factions. I am not here to make an argument on that front, just use it as a source of contextualization. The primary one being that the location is discrete, but no less important is the direct emphasis on the rest of the outside world. Disagree all you want, but you can’t reference Black Mesa directly if there isn’t Black Mesa. If you have Black Mesa, you have Half-Life. This is a contained facility, and the second installment makes that clear.

Further, the story being portrayed is a complete one. This was somewhat tempered by the fact there was a second game and thus the ending was edited, but then the second game presented a complete ending…unless a third game ever gets made. Of course, that isn’t likely to happen, since it is a Valve product. Only Left 4 Dead gets that sweet, sweet third game action…probably. Even that isn’t confirmed yet, though it might be true by the time this is published. Regardless, the story of Portal has a clear beginning and ending. Being a completely contained story with an endpoint – even if the both points are a bit clouded – runs counter to the purpose of the megadungeon as a center of pure exploration. However, the game is clearly a total experience that takes place inside what would easily be classified as a dungeon in any fantasy game medium. The size and scope of such is also much larger than a standard dungeon. Being neither a standard dungeon – even a large one – nor a megadungeon leaves Portal as a great example of a kilodungeon from a complete play perspective.

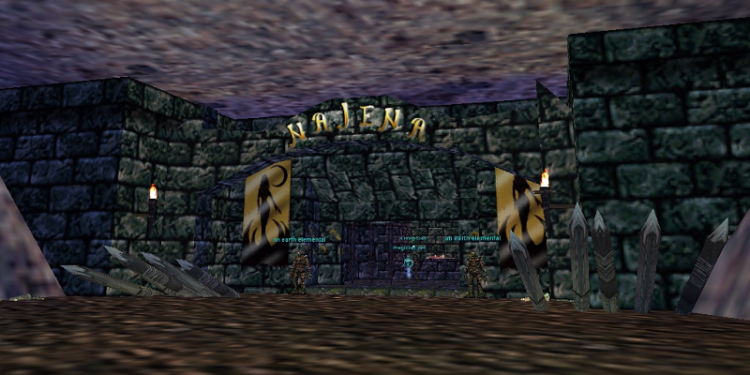

Nuh-jean-uh? Maybe? I’m not a Dark Elf.

For a more integrated – rather than standalone or module – play perspective, Everquest provides us with many examples. One of my favorite dungeons in the original game was Najena – a dungeon set just off of the volatile mountains of Lavastorm. As with any long-running project with multiple writers, the lore around the dungeon has changed over time – particularly with the introduction of Everquest 2. However, I will primarily be focusing on the initial implementation because it illustrates the point quite well without the additional dross. You approach the dungeon through giant doors that are in disrepair and bear a strange shadowy symbol upon them. Inside, you are greeted by copious piles of bones that reveal themselves to be skeletons, and numerous patrolling ogre guards. There are also strange tentacled creatures that are made of some sort of jelly and are shaped like cones. Are you make your way into the area past these front guards, you find a finished fortress that is distinctly worse for wear. The inhabitants are almost uniformly dark elves, though there are numerous elementals and undead that are still present. You do not have free reign over the area. Instead, you must recover a series of keys from the different areas in order to move to the next area – eventually culminating in reaching the lair of the magician Najena. Each of the areas leads to the next, but each of them also tells a distinct story around what is occurring in that area, and how it plays into the overall story of the dungeon. It is also worth mentioning that this dungeon only ties into the mythology and story of the dark elves and their history, and doesn’t pose a larger immediate threat on the world. This is just a secluded lair for these arcanists to do their work. It could be completely ignored, the dark elves would go about their work, and the end of the world wouldn’t be imminent. It might be on a really long time line, but probably not for at least a few expansions.

The main areas of the dungeon are the jail, the astrology room, the arcane warrior training facility, the dark arts room, and the ritual room. Each one tells a single story that contributes to the larger story of the dungeon. This goes beyond “each room has a purpose” that many dungeons possess thanks to the nature of the gameplay itself. The jail is certainly a jail, but the story of the jail is the story of the ogre guards attempting to marshal the prisoners therein until such time as the dark arts room is ready for them. After whatever occurs in the dark arts room – the story of the dark arts room is tangential to the jail – the ogre guards escort the “prisoners” back to different cells. The cells, while still in the jail, have a different set of keys and only certain ogres path over to it – the officers, specifically. While this is a minor thing during the course of a video game play through, it is a clear story being told from the dungeon perspective. There is a holding area that fresh prisoners go into, and these – despite who they might be – are safe to guard with normal troops. However, once we take them to the guy in charge of dark magic, we no longer trust the prisoners to be with others, and we also don’t trust our own people to guard them. Thus, whatever is being done to these prisoners is beyond what even an ogre might consider okay. Also, the jail is then divided between the normal holding area and the black cells that no one ever wants to venture to. Again, in the course of a video game we are talking about just killing a few dudes and running around, but it’s a very different scenario in a table top. Figuring out what is going on in the jail, who is being kept where, who knows what, and so on is enough to occupy a significant portion of a story in its own right.

While you can certainly do this in a dungeon regardless of size or scale, each of these kilodungeons are designed in order to be compartmentalized in that exact fashion. Exploring the mundane part of the dungeon (entrance to jail) comprises about 20% of your total leveling experience, while the rest of the kilodungeon ends up being another 40%, for 60% total from this one place. In both modern video games and in D&D, that’s a lot of your total play experience. If it was going to be that much of your play experience, there might as well be a lot going on, right? That’s the general idea, at least. Everquest was designed so there were copious amounts of these kilodungeons spread all over the world, each dealing with discrete or area-limited elements. This meant that in any one or two full character playthroughs, you wouldn’t be able to experience even a meaningful portion of the content. For the sake of replayability, this was imminently desirable. In the case of tabletop gaming, the desirability might be incredibly varied. One group might want to fully complete a kilodungeon – something that could be done – while others might want to pop around and check out parts of several, and yet others might want to only explore certain parts of one and then get to other matters. Luckily, kilodungeons can easily provide any and all of those opportunities.

Why I Care about the Kilodungeon

I am a huge fan of the kilodungeon. I love being able to get a strong sense of exploration and lore, but also being able to feel like I am completing things and can “solve” the dungeon as I continue through it. The scope of the kilodungeon is almost always a “local or regional” concern, allowing threats and content to be a bit more individually tailored – but still fully fleshed out. A goblin-held area is more than just a few camps or forts that could be easily taken out by the locals, but still less than a sprawling underground goblin society that has existed for time immemorial. Equally as important to me, the interaction with the environment is player-driven rather than story-driven. While the story is there – and hopefully excellent – it’s the player’s curiosity and drive for exploration that triggers the events. It’s not a villager asking the players to go into the spooky abandoned castle to retrieve something. It’s the villagers telling the players there is a spooky abandoned castle that was rumored to be a haven for vampires, but no one goes there anymore. Once you get there, the story of these vampires is then brought to life and told over the course of the exploration…unless you don’t want to continue exploring. That isn’t to say consequences should be left behind once you start decide to leave. Just that the story of the place itself continues on as it does, rather than becoming a guiding force in the rest of the narrative of your play.

This approach is certainly not for everyone and every game. However, it is a shame I don’t see more of this style being discussed or readily available for consumption. Sure, adventure paths with castles and dungeons are numerous, and even a variety of megadungeons are there for consumption. Standalone, large scale environments that contain stories within them that exist solely for the sake of exploration are much less common. I’m a huge believer in optional story and lore engagement. I believe that when players choose to engage and explore they often take more ownership of the story and become more invested. For me, it harkens back to these kilodungeon in games and my drive to discover the stories inside of them. The stories are there for the taking, but it’s not required. If I want it, I can pursue it and make progress or not as I see fit. If I don’t , that’s on me. It’s also not going to burn down the story of the game or destroy the world in some way if I don’t want to complete it or engage with it. It’s all personal. When it comes to tabletop storytelling, isn’t personal investment and story one of the things we want most? If it is – like it is for me – then consider implementing a handful of kilodungeons. You might be pleasantly surprised how your group responds.