Feedback Debt in Tabletop Games

Way back in September 2017, I wrote about technical debt and why it matters for tabletop design and play. While I remain happy with this piece, I’m disappointed in myself for not writing the necessary follow-up sooner. In a lot of ways, it’s the more important article to write. Technical debt doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It exists in a codependent relationship with its partner in crime – feedback debt. Feedback debt is a direct contributor to technical debt, and acts as a bellwether in many instances. The reason for this is feedback debt focuses on the most important aspect of tabletop gaming – the people.

What is feedback debt?

Feedback debt is the cost of future psychological safety for the conversations you are currently having. In other words, it’s the cost of saying nothing. Just like technical debt, feedback debt accrues for myriad reasons – and usually not out of any ill intent. While I am sure there are edge cases, I don’t believe programmers sit around rubbing their hands together and cackling at the idea of not fixing a user-experience damaging bug. Likewise, I don’t think the vast majority of people delight in purposefully withholding critical feedback that impacts their personal and professional lives.

Feedback debt tends to occur because we are unable or unwilling to give and receive meaningful feedback. Part of this is cultural, of course. The American South, for example, is particularly feedback adverse. One of the greatest example of this is, of course, the phrase “bless your heart.” While you certainly can say it in a sincere way, it rarely is. Instead, you say it instead of saying “you idiot’ or something similar. Saying “you idiot” isn’t particularly meaningful feedback either, but the facade of civility and niceties are a way of life in the South. You’ll have an hour long conversation over coffee where nothing is really said. This is to say nothing of the political conversations you avoided over the holiday season.

Psychological Safety

It’s important to understand psychological safety before getting too far down the feedback debt-rabbit hole. The quick and dirty summary of the concept is the ability to show your true self without the fear of it impacting your social or professional standing. Studies have shown that when you are able to just be yourself, you perform at a higher level. When your entire team – be it your gaming group or at work – feels this way, the entire team performs at a higher level. This doesn’t mean that everything you do or say is beyond reproach. It usually means the opposite. You will suggest ideas, the group discusses the ideas, and it might or might not move forward. The group discussing the ideas will be respectful, and discuss the idea rather than the person.

Being openly antagonistic, shocking, or inappropriate for the setting decreases the psychological safety of the group. For example, attempting to discuss your sex life in intimate detail at the office is likely to decrease psychological safety in typical workplace settings. Discussing it with friends over dinner is probably fine – depending, of course, on your friends. Sharing stories from your dating life with your coworkers, however, is likely to increase psychological safety as you are forming personal connections. In all things, it’s about the context.

Gaining Feedback Debt

Most feedback debt occurs in one of two ways. The most obvious is being in a psychologically unsafe environment. If someone within your group berates you for something – regardless of it’s a mistake you made or just an idea you suggest – this creates a psychologically unsafe environment. Not only do you worry that you this person will berate you again if you speak up, you now internalize the fact that no one sticks up for you or stands up for you on your behalf. In this case, you don’t want to tell people what you think, even if they aren’t the ones who are the overt issue. You keep your head down, and don’t say anything.

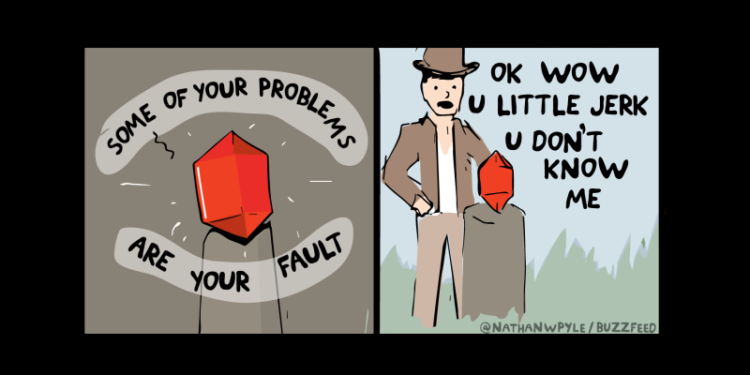

The second way is the exact opposite. You don’t want to say anything the other person will perceive as negative because you care about them as a person, and want to avoid hurting their feelings or potentially causing a conflict. From a purely anecdotal perspective, this is the version that more frequently occurs. You don’t want to confront a friend about an issue they are experiencing, simply because they are your friend. Unfortunately, every time you don’t tell them something, it gets harder to say something the next time. After enough times of avoiding the topic, you reach a critical point where saying something is certain to make the debt come due. You speak up about the topic, and your friend says, “you’ve felt this way for how long and you didn’t tell me?” After that, it’s off to the races. That trust and safety you’ve built shatters, or at least experiences some damage.

Feedback Debt in Tabletop

Tabletop gaming has a lot in common with a dinner party. Some tabletop games are like a potluck. Everyone contributes something and any one person isn’t really in charge outside of being a driving organizational forces. Other games are like a formal dinner. The participants show up and focus on the ritual of dining and experiencing the food on offer. Still others are a casual dinner where someone is hosting and preparing food they love more than any other food in the world, because they want you to have the opportunity to experience that same love. In all of the instances, telling someone the food sucks isn’t a good way to get another invitation. Of course, not saying anything leads to a situation where everyone prepares tuna for you even though you do not like the taste of tuna.

D&D can be like any of the above, and there is no wrong way to enjoy it. That said, there are plenty of ways to create situations where players feel uncomfortable, upset, or unwilling to talk to you about how they are feeling. Having a session zero where you establish table rules is a good way to mitigate this upfront and help create a psychologically safe environment, but it’s not a silver bullet. Players and DMs have to engage in meaningful feedback consistently in order to maintain this environment.

Did You Have Fun?

When a session is over, have you ever asked or been asked, “did you have fun?” Of course you did. It’s a group activity, and everyone is there to have a good time, right? I have a follow-up question for you, has the answer ever been “no,” and you either weren’t told or didn’t tell the person asking you? If nothing else, I’m quite certain the answer at least sometimes is “yes and no.” You probably like something and don’t like something else, resulting in a mixed experience. It could just be a minor thing you don’t like, so you don’t think it’s worth mentioning. However, by not mentioning it, it’s not going to magically become known.

The flip-side of this is, when you ask the question, do you really want the answer? I think most people probably do want to know the answer, but might be bad at receiving the full truth of the information. No one wants to do a bad job, after all. However, receiving feedback can be extremely difficult. It’s hard work to give and receive meaningful feedback.

What is Meaningful?

When you ask people if they had a good time, are you doing it in front of other people? Do you know if they feel comfortable answering in front of the rest of the group? How are you going to handle it if the answer is “no?” Do you know why the answer is no? Do you know what would make the answer “yes?” Is it clear you have the best interests of the entire group in mind? These are all things to consider when thinking about meaningful feedback to “did you have fun?”

Saying “no” is not meaningful feedback. There is no opportunity for growth or improvement. A better answer might be, “I enjoyed the majority of the game, but I didn’t enjoy the political intrigue this game.” Expanding on that in more detail is, of course, even better. Something more like “I enjoyed the majority of the game, but I had difficulty with the political intrigue this game because I’m playing a fighter who doesn’t care about politics” is more specific and valuable for knowing what the player is looking for. However, it doesn’t really have the entire group in mind, as it makes no mention of the rest of the group, or how less political intrigue might benefit the game.

An example of even better feedback might be, “Thank you for asking. I enjoyed the majority of the game, but have difficulty engaging in the political side of the story. I’d love for there to be a catalyst to help my character grow.” The feedback acknowledges the fact the person asked, doesn’t seek to place blame, and is focused on making the experience more enjoyable for everyone at the table. The higher the engagement of players, the better experience for all those involved – DM included.

Real Talk

Feedback isn’t a license to be an asshole. Full stop. However, giving and receiving direct feedback is important. If after a game someone tells you, “every NPC we have to rescue is a woman, and that upsets me,” that’s meaningful feedback. They didn’t couch the statement in niceties, but they are taking a personal risk to give you that feedback. It might be difficult to hear that, particularly if you didn’t know you were doing it. Another example might be doing voices for characters. Overall it helps immersion, but if a player says, “the voice you use for the shopkeeper makes me uncomfortable, as it sounds like a racial stereotype,” then take that at face value.

Believing you and the players have good intent is crucial for this to work. The players WANT to keep playing with you and have a good time. You WANT the players to have a good time. You all WANT your game to be the best it can be. When someone gives you feedback, they are putting themselves at psychological, social, and professional risk. They are taking the time to reach out and work with you. Likewise, when you ask, you are taking the same risks, and telling them you value what they have to say.

Some Caveats

Feedback shouldn’t be mandatory. If it’s something that’s required, and not something the parties are committed to doing, it isn’t going to be meaningful. Likewise, telling someone how you would do something isn’t going to be meaningful. By definition, that person isn’t you. Your feedback should help them grow and become better. Aping someone else is only ever going to get you far. It can help you further define yourself, but if you aren’t being your authentic self, then you are going to damage the psychological safety of the group.

Further, receiving feedback doesn’t necessarily mean you need to incorporate it. It can be the right call to say, “thank you for the feedback and your honesty, but I don’t think that’s the best course of action.” Of course, if you say this every time or in such a way to discourage the person giving the feedback, you might not get feedback any more. Still, blindly accepting and agreeing with everything only creates more feedback debt.

Final Words

I know it’s hard. I know that it’s scary. It might not be something you want to do right now, and I’m not here to make you do it. If you don’t want to do it, no amount of discussion is going to change that. You have to want to participate in something like that, and work with the other people in your groups to make it a reality. There will be some missteps. There will be some hurt feelings at first, but being open and honest should hopefully mean you apologize when you need to apologize.

If nothing else, I just want you to think about how important this all is. How poor feedback, withholding feedback, or not soliciting feedback contributes to other, systemic problems. Think about this and go back and think about technical debt. It should hopefully become obvious how the two interlink. Hopefully it makes people more willing to engage in these potentially uncomfortable areas and bring about growth and psychological safety.

Trust me, I know it’s not easy. I’m still working on it every day.