Tribal Knowledge: Player Handouts and Other Ephemera

Do one concerning ‘props’ and table topping. Like your awesome model you built out? I know some people actually dress up salon style as well – or have a personal prop – like a hat.

–Perturbed by Proprieties of Personal Props

Dear Perturbed,

I love text props, maps, and other game-related ephemera in tabletop gaming. They add tactility, a physical object for later reference, a moment of surprise… there’s a lot going on here and I love every bit of it. Let’s talk about some specific cases. With pictures, in some cases!

Text Props

By far my personal favorite, because as any of my friends will tell you, the fantasy of being a sage, versed in high and secret lore (link points to a PDF), is my favorite thing in gaming. A text prop is really any handout that is covered in text. The more clues and references to other parts of the game you can justify building into the text, the better. Every time you touch on something that the players have heard about before, they feel good for remembering, and they have an easier time remembering the new piece of information because they have context for it.

Some players will never remember the lore you put in front of them. It may not be what they enjoy in a game, it may have been too long since you dropped the first piece of information, it may be that they’re genetically predisposed to jump to wrong conclusions (I know people like this), or any other reason. Don’t take it personally – as long as they’re contributing to the group’s fun and having fun themselves, they’re fundamentally good players. (You may need this lesson less than I do.)

But I digress. There are as many kinds of text props as there are reasons someone puts pen, quill, or pricked finger-tip to paper (or parchment, or papyrus). Journals and correspondence are by far the most common kinds of text props, but here’s an off-the-cuff list of other kinds:

- Grocery lists

- …that hide the secrets to an ancient conspiracy.

- Musical notation. Maybe the tune is the key to opening a magically locked vault.

- Broadsides posted around the city

- One of my players, may her name be immortalized in song, created just such a broadside: a wanted poster denouncing an NPC that the group really hates.

- This is a great way to announce royal decrees, traveling carnivals, and merchants selling rare and uncanny goods.

- Contracts

- These are even more fun if your setting has contracts that are mystically binding, because now the PC can figure out what to trick an enemy into doing so that they suffer the contract’s penalty.

- Theological disquisitions and screeds

- These are a mouthpiece for a villain’s religiously-motivated perspective. It’s often hard to show your players why the villain does bad things, so this kind of thing can help.

- Detailed logs of inquisitorial hospitality

- When writing this kind of text, understatement has all the power. What you say heightens the tension or turns the stomach; what you do not say chills the blood.

- Invitations to tea

- This is a subset of correspondence, but if calligraphy is one of your skills, this is a great way to make your players feel like the world notices them. Depending on the source of the invitation, the emotional response might be a sense of reward or dread, but it’s almost always a useful response.

- Don’t forget about things engraved on walls and other architectural features. You probably don’t want to just hand the players a section of wall (but see below), so creating an image of it on paper is close enough for good gameplay.

Make sure the PCs care by providing one or more clues to the adventure – usually that means an antagonist’s plan. Get maximum mileage by name-dropping other setting elements, not as red herrings but as ways to show the PCs how big your world is.

Normally I am in favor of all the aging and doctoring of text props that one’s imagination grants. Fake blood is a real pain at the table, though, because it never loses its tackiness. Even the slightest drip onto a book or character sheet is as good as permanent. (Fortunately dice, clothing, hands, and tables can be washed.)

Maps

I assume that there’s no sighted person in the whole of fantasy gaming who doesn’t think maps are cool, as a matter of principle. D&D is deeply bound to a subgenre of fantasy fiction called map fantasy, after all, and having a gorgeous setting map is sometimes all you need for a good game. They come in all different scales, of course, any just about every common map-scale makes for a good handout. This article is not intended as a guide to best-practices fantasy cartography.

- Cosmic-level maps give your players some clues about the likely shape of high-level play, possibly including the sources of world-threatening evils. Even better if it includes clues on how to get to some of those extraplanar locales.

- World-level maps – perhaps surprisingly, it’s more common to see an accurate cosmic-level map than an accurate world-level map in fantasy gaming, because the typical medieval setting has huge amounts of Terra Incognita for players to go explore.

- As a result, world maps are great for pointing giant neon arrows labeled “Here There Be Monsters to Stab.”

- It has always been easy to get humans interested in finding out what’s beyond the horizon. We are explorers, and I think a lot of us play games to enjoy that feeling in imagined worlds.

- Continent-level maps show the essential game area – everything in reasonable reach before 9th level, and the area that the PCs care most about saving from late-game cataclysms.

- Mysterious, exotic locales on this scale look close enough that the PCs could get there if they wanted it bad enough. In my experience these remain aspirational until the DM makes them go there, because like everyone in the world, PCs are looking for the low-hanging-fruit goals first. There is no journey of a thousand miles on foot or horseback that is “the low-hanging fruit.”

- Kingdom-level maps start to feel kind of intimate, unless we’re talking about a huge empire. This behaves a lot like a continent-level map, but slightly earlier in the campaign. The neat thing about this scale is that it shows things the PCs could receive – manors, mayoral office, or baronial estates. Even the kingdom itself, though that’s sure to be a retirement option unless you’re playing Birthright. (You should be playing Birthright.)

- Mysterious, exotic locales on the kingdom scale have a much higher chance to be the party’s low-hanging-fruit option, in which curiosity trumps drive to do anything else.

- The most common application of any scale smaller than kingdom-level is the treasure map. Everyone loves a treasure map, because its name literally combines two of our favorite things. Is there a more iconic expression of adventure than a treasure map? I think not.

- I think that the best treasure maps include at least one puzzle of some kind, whether that’s figuring out where the map starts, or how to reveal the Cirth runes (moonlight, one day a year; thank authorial convenience Eru Ilúvatar that it happens to be tonight).

- Maps of a city or town are neat, but not immensely necessary to players in most games.

- I kinda wish someone would create a map of the Greater Metro Atlanta area that didn’t worry too much about street names (spoiler: they’re all Peachtree), but pointed out interesting places to have adventures. I-285 is the perilous moat surrounding our fair city…

- One great use for a city map might be marking the safehouses of a spy ring.

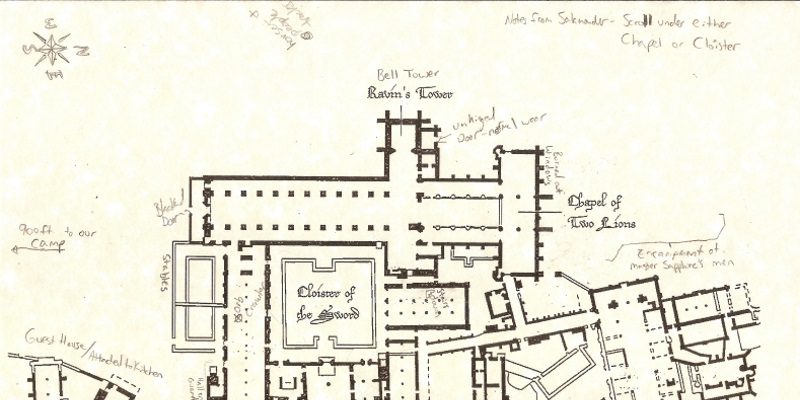

- Maps of a dungeon are awesome. I got great mileage out of giving my players a partial map of a dungeon they were about to explore, and letting them fill in more details over the ten sessions they spent exploring. This gave them a foundation for their information, in a way they didn’t have to remember or read from obscure hand-written notes. A map was a good idea here because maps are a good way to store information.

- Of course, maps can be wrong, too. Get PCs used to trusting the map, right up to the point that they overextend themselves and get cocky, and then BAM! POW!

- For the real magic, create areas that the PCs can meaningfully change in gameplay, whether it’s clearing or collapsing a tunnel, getting ancient machinery running again, or restoring a healing altar. PCs have learned something, written it down, and taken the setting into their own hands to change it.

- If you do any research into ancient or medieval mapping, it becomes clear that they weren’t always concerned with the same kinds of depiction that a modern user might expect. Maps are about storing and presenting data, which can include extensive propaganda aims – such as deliberately distorting the size of kingdoms so as to enhance or diminish their importance.

There are a lot of great fantasy cartography resources online, from Dyson’s Dodecahedron, to a G+ community dedicated to fantasy maps, and the WorldBuilding School. Or you can search for floorplans of castles, monasteries, and other ancient structures, which is what I did.

Chests and Coins

As compared to LARPing, one of the things that I’ve always missed in tabletop gaming is a sense of cash loot as anything more physical and meaningful than a number on a character sheet. The surreptitious intrusion of fantasy into modern culture and design does you some big favors here, though: you can get a surprisingly credible treasure chest for $10-$15 at Target, Ross Dress for Less, and all kinds of other places. Any box that doesn’t look classy enough for your purposes just needs a coat of stone spray paint.

There have been Kickstarters of fantasy coinage, but those can still run a bit pricy for something that may not come up any too often. A better lowball solution might be a colossal number of wooden pogs and cans of gold, silver, or copper spray paint. Pick a contrasting color to paint on denominations, and maybe a stamp for the reverse side. It’s a lot of work to get up to a full chest of treasure, but the sense of volume and heft go a long way with the imagination.

Tiles

As a game-runner, I have an unhealthy fondness for puzzles, even as they’re often a headache to develop in the first place. As it happens, home-improvement stores sell boxes or sheets of stone tiles for various décor purposes, because again: stone is fuckin’ classy. Think of these as a jigsaw puzzle waiting to happen, so the PCs have to construct a message or an image with little more than relative context. Personally, I’ve had much better luck with text than with images; text puzzles usually take just the right amount of time that players engage with it, without steep difficulty spikes or long spans of confusion that cause frustration.

Images or messages on tile are interesting even in non-puzzle formats, because we all saw the odd-numbered Indiana Jones films and wanted to be adventuring archaeologists. For that matter, broken ceramic is amazing for this. It’s a much more involved process to paint pottery with images that convey meaning, unless you happen to be a graphic designer and/or ceramics artist by trade, but it’s phenomenal when it works because it’s such an immersive moment.

Another great use of tiles is as individual handouts to represent magical runestones. In a tabletop game, you could absolutely use such runestones as consumable items to modify spells. This would keep the DM from having to make too many of them, in theory, but systems for getting PCs comfortable with using their expendable items is well beyond the scope of this article.

In summary, tiles are worth a look for a lot of purposes, and they’re a little spendy but not unbearably so. They are heavy, to carry to game sessions in any great quantity, but they bring visual and, er, tactile interest. Advice to the GM: offload them onto the players posthaste, so the players have to haul them around.

Costuming… and Makeup?

I can accept that some people play tabletop games in a costume constituting one or more pieces. It really wouldn’t be for me, which is kind of funny coming from someone whose twentieth year of boffer LARPing is this September. Of course, I’m also the GM in the majority of the sessions I’m involved in, and there’s no time for the GM to change costume accent pieces. The most I can see doing with this is maybe a fancy hat for a swashbuckler or a T-shirt with a character-appropriate reference. (For those wondering, all zero of you, my typical game-running uniform is my Harbinger of Doom T-shirt and blue jeans or shorts.) I’m not here to judge people who feel otherwise about it, but I’ve never been part of a group that emphasized at-the-table costuming pieces.

Because it’s Ash Wednesday as I write this, I wonder how things would go if marking players with makeup of various kinds to signify lasting game effects would be interesting. Dramatic, near-permanent effects, that is, not transient conditions. It would be a reminder of the effect every time people looked at the player. I’m thinking of things you can manage with black liquid eyeliner or a metallic Sharpie, mainly. (Cybernetic circuitry… even in a fantasy game, because… I dunno, maybe you had missing pieces replaced with iron golem bits? The Chirurgeon General does not recommend this!)

Why is this less weird to me than wearing a piece of costuming, one might plausibly ask? A fine question, and if I ever test this out, I’ll let you know if it’s actually less weird.

Terrain Pieces

This is more for combat grid work, but you can also have a good time by putting work into building a terrain piece for the action. Now, there are more online sources on terrain-building for wargaming than you can shake a red plastic ruler at, so I’m… not really speaking to that grade of craftsmanship. The terrain features that Stands-in-Fire helped me build were designed with usability rather than flashy good looks in mind.

For a session back in November of last year, I had decided that I really wanted to wow them with this one and try some things I hadn’t ever done before. The core of my concept was to create terrain for an area that the PCs could explore at length, with a lot of vertical movement, and maybe a giant skeleton. I felt like building the whole thing into a large cardboard box would be really nice for transporting it, and I was satisfied to make it a narrow box canyon.

I went to a nearby Michaels and looked for interesting materials. I bought a bunch of styrofoam. (This is not all of it, as you’ll see.)

I had an idea that I would cut one piece of styrofoam to make two “towers” (shown above). I also cut longer sheets of foam into smaller sections and glued them together to form a multi-level tower.

I glued craft foam to the styrofoam, and painted the craft foam gray. I made the tower’s stories very tall so that our not-to-scale hands could move minis around inside. Despite my efforts to make the tower’s legs the same length, it didn’t wind up terribly stable, but then I also didn’t try to glue it down, and it was Good Enough. I also drew on staircases with a Sharpie.

Still, this involved a lot of styrofoam for one little tower. This was not a good method for realizing my vision, unless I wanted to spend a lot more money on styrofoam. (I did not.) This is where Stands-in-Fire comes in. He suggested using a different material: foamboard, which will be familiar to every who has ever made a science fair triptych. For the legs of the towers, he suggested using dowels. So we did.

These I likewise painted gray on the player-facing surface. We made them partially one layer (two stories tall, as Americans count floors) and partially two layers, as you see. The point, of course, was to encourage more vertical movement.

Finally, I still had this styrofoam cone, which we cut in half… but it didn’t look all that great as towers. I wanted to get something out of it, though – this piece was as expensive as about half of the rest of the project put together. So I cut a sliver more from the broader piece and glued craft foam to it, onto which I painted a door and two runes, in red. I wasn’t 100% sure what the mechanic was going to be here, but I figured I’d come up with it at the table.

(In this image, all hell has already broken loose and the PCs are pretty sure they are doomed.)

I started buying all of this stuff right around Halloween, and I had also picked up a little purple light, figuring that a little purple light would surely prove to have some interesting use. (It did.)

Conclusion

Props and handouts can do a lot to elevate an encounter or session from good to great, anchoring the events in everyone’s minds for years to come. More than anything else, this is because they appeal to more senses than just auditory, and even good auditory learners probably remember more when there’s also something to see, touch, and for the love of God, stop eating that… examine.

There are many more ways to go with this as well, but I want to hear what my readers have tried. Whatcha got, you clever and winsome devils?