Tribal Knowledge: You’ve Got to Know How to Ask

This article is about a very thorny subject in gaming: what does it take to get information out of someone who doesn’t want to give it to you? I’ll be attempting to address this point within both LARPing and tabletop gaming, as the visceral immediacy of LARPing intensifies the issue. There are interlinked issues of information control, the grimdarkness of the setting, the players’ and DM/NPCs’ conceptions of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” mind-control magic, and whether any threat suffices to get the PCs to back down.

Also, a caveat to the whole discussion: nothing that I’m going to discuss here is necessary or helpful if the DM and the players can easily come to consensus on the issues. Rules exist to guide the flow of play when the sides of a conflict can’t agree, or when uncertainty in the outcome is desirable. This is doubly true when applied to rules governing social encounters (or, in the case of interrogation, anti-social).

What can the PCs do to get information the NPC doesn’t want them to have?

- Persuasion Checks: If you’re not careful with the Diplomacy or Persuasion skill in various editions of D&D, it becomes awfully similar to mind control. In 3.x especially, this ran to the point of a highly specialized bard being able to stop combat with any sentient foe if the bard had a chance to speak. (To be fair, Saruman was like this.)

- Mind Reading/Control: Being able to read or control a villain’s thoughts is just about carte blanche to wreck the rest of the villain’s plans. This is obviously a lot of fun for players in the short term and rewards creativity about as thoroughly as one could want. It might also wreck everyone’s fun in the mid-to-long-term.

- Bargaining: From the DM’s perspective, this is the best one, because bargains can have costs. Persuasion might handle this. Many Powered By the Apocalypse games have moves written around this, to frame compliance clearly.

- Trickery: Some percentage of the time, the Deception skill or some quick thinking lets PCs trick NPCs into revealing information they had not intended to reveal.

- “Enhanced” Interrogation: Either through description (some tabletop games and every LARP I know about) or skill checks; typically Intimidation but sometimes a separate Torture skill (as in Hackmaster).

When can the GM just say, “I don’t care how high you roll, this guy is more devoted to or frightened of the guy he would be betraying”? In D&D, the GM has the option of pricing the DC out of the market, since most skill systems include a way to define something as “impossible.” This sometimes fails to take into account all of the bonuses and situational modifiers that PCs could stack up to reach those DCs. There are a lot of additional debates about GMs asserting this level of control over the course of the narrative; railroading is the less charitable term. My personal feeling is that as long as the GM shows restraint and does not insist that all of the NPCs are too (fill in quality here), this is probably okay. If the PCs have been stymied a few times by hardline loyalists, let them find a weak link in the organization. Including “these guys are known for not giving up information” as part of the exposition on the group (preferably before the first serious conflict) can do a lot to help it feel fair, because at least that way they can make other plans and they don’t build up expectations that are going to be thwarted.

The big problem with this – and with any rules for social interactions – is that a significant percentage of the players I’ve met over the years believe their characters should never be forced into any action they didn’t choose, even if those players habitually force NPCs into actions that the GM didn’t choose. I am one of those GMs who thinks this is a strange view of the game, but I tend to accept that PCs will feel that this ruins their fun.

Okay, so there are some problems with skill-based questioning in tabletop games. What about non-rules-based questioning in LARPs? Hypothetically, NPCs are governed by their personal interpretations of their briefings, which will often instruct them as to where they stand on the loyalty-to-boss/self-preservation spectrum. There’s a bit of a divide, though, for NPCs played by the staff member who wrote them; since no one assigned the role to the staff member, there’s no distance from the role being someone else’s creation, and the person playing the role isn’t really answerable to anyone but the other game-runners. (Maybe there’s a similar feeling when the director also acts in a film?) In such cases, it’s especially important for the staff member to check ego at the door.

I have heard anecdotes of torture scenes from various games; in one particular case, a PC was the victim and the bad guys were trying to extract information. The one I’m thinking of here is actually a MUSH, but a lot of the principles of live-action play apply here. Despite that game having an explicit Willpower mechanic, one player insisted that his character would not break under torture, no matter the extent or duration thereof. This gets into a whole field of other problems, such as players and Plot not being able to agree on what the “badass level” of the character is. Can a player just decide that she is an uber badass who fears neither death nor pain? A character who is constitutionally incapable of backing down is great for power-fantasy gaming, but that really kind of needs to be a single-player game. Otherwise, the GM is in the position of trying to force the player to take threats seriously; in my experience this can only lead to dick-waving of the worst order. The thing is, of course, that the Nuclear Option is always on the table for the GM. I feel that the player is to some extent obligated to carry out some doublethink: while they should portray a compelling and (in most games) heroic character, I feel that they are obligated to approach the setting and the threats therein as though they were real – that is, to suspend disbelief.

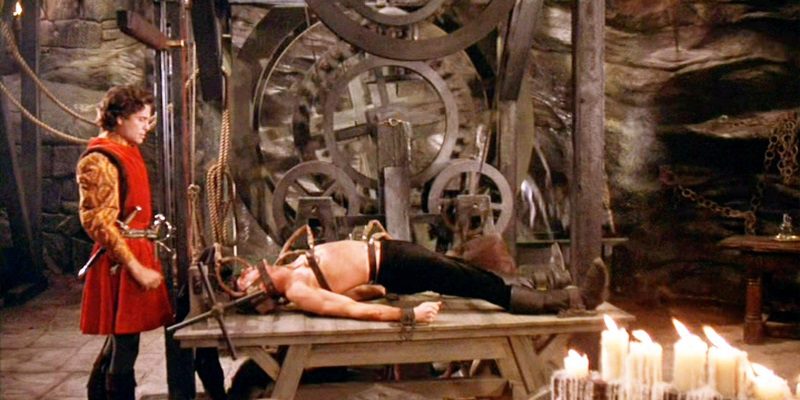

There are also those times that PCs decide to torture NPCs. Obviously, most NPCs aren’t there to seem heroic, and don’t need to show how badass they are by withstanding torment. If they did, they’d risk upstaging the PCs; even NPCs that are badass and should be awesome should take it easy on that front. But that isn’t the serious problem; the problem is that especially in a live-action environment, player use of torture does kind of permanently darken the character’s and the game’s tone. I believe that even players who regard their characters as shady or hard-edged still feel… grimy, after a scene of describing the horrors they are wreaking on this other character. In brief, it draws the game toward either “wandering band of sociopaths” or “town full of sociopaths.” Look, I said upfront that this was some ugly stuff, right?

There’s also an outright bizarre belief, among players who would consider such tactics, that they might succeed in gaining useful information. There might be arguments about how real and gritty this is, to which I can’t help but point out that actual interrogation techniques of this kind are good for confirming what you already know, and for securing confessions that may or may not have any basis in fact, but that’s kind of it, and those aren’t the ways I tend to see it used in games. Oh, and another thing – actual “enhanced interrogation” takes a lot of time and patience. It’s not the kind of thing you’re going to finish in a single episode of 24. DMs can probably feel justified in informing players that breaking down the target’s will might take weeks of work that occupies most of their time… don’t have you have kind of timeline to worry about?

Anyway, let’s sum this up by saying that I don’t like for PCs torturing NPCs as the most pragmatic means of gathering information, and I don’t like NPCs torturing PCs because there’s almost no way to make the scene cool. Dust to Dust has thus far stopped at alluding to one; we told the player, “The bad guy has been performing bizarre kinds of experiments on you, etc., for a subjectively very long time. When the scene starts, the villain is out of the room. Play it kind of however you like.” We had an excellent result from that, which I credit half to that player’s personal style meshing well with what we wanted from the scene, and half to the game “fading in from black,” if you will, to show the results but not the process. Also, the player went nuts on bruising, dirt, and wound makeup, which did a lot to sell the scene to everyone.

So what about mind-control magic? Many games have Suggestion or Charm spells that, as written, should make life awfully easy for the inquiring party. Every argument that one can reasonably have about player autonomy is heightened with the introduction of mind-control magic. Mind control (much more convincingly than brainwashing) is literally de-protagonizing: when a comic book writer wants to turn a superhero into an antagonist for an issue or two, mind control and brainwashing (basically, the supernatural option and the mundane option) are the go-to solutions. Seriously, the more time you spend in the comic-book world, the more likely you are to be someone’s mental puppet. There are players in the world who don’t mind fighting their friends for awhile; one of the most thrilling events of my LARPing career was a span of eight or twelve hours in which I was playing a bad guy who looked exactly like my character, which for my intents and purposes was the same as being mind-controlled. Others don’t see it that way, and find the concept of mind control as deeply disturbing as anything that the game could do to them.

The problem that I’m concerned with here, though, is that mind control has such varied uses: information-gathering, infiltrating an organization, gaining an ally (and removing an enemy) in the midst of combat, or any other way players can think to use someone with absolute loyalty whose physical well-being is explicitly not useful. There’s an argument to be made, then, for including limited-duration mind control (possibly with some added paralysis) so that it is really only useful for information-gathering, on the principle that this both attaches a mechanical cost to the effect, and lets game-runners sharply discourage the use of torture. On the other hand, this offers nothing to the player that finds mind-control effects to be game-ruining or outright triggering.

One interesting solution I’ve heard comes from the Forest of Doors LARP, in which the Etiquette skill has the ability (once per day) to discern “what the proper or expected action would be in that situation.” To curtail the use of force to extract information, the staff interprets this definition to include how best to get information from an individual. Players are much more careful when it comes to expending a per-day ability, and the marshal’s direction points them toward bribery, flattery, threats, actual force, or whatever else.

This is an argument for pushing charm person and suggestion to higher spell levels in D&D, and maybe adding further limitations. The current limitations of “friendly acquaintance” (or, in some other games, “things you’d do for your best friend,”) are highly subjective, given that the spell represents force as a solution to a problem. I like that the charmed condition still relies on Persuasion checks in 5e – I like it when skills matter! Going straight to the desired end result without a skill check should be the province of higher-level magic that represents both work and greater opportunity cost. This is also why I’m super uncomfortable with the breadth of information that a playtest Awakened Mystic can glean.

Let me not end this without talking about Apocalypse World, and by extension a lot of PBTA games. Two of the basic moves – that is, actions available to everyone – are Seduce or Manipulate and Read a Person. These moves are explicitly about controlling other people and gathering information in social scenes. There’s also Go Aggro, which can end with the target telling you what you want to know, or what you want to hear, but that sounds a lot less reliable than the first two I listed. Seduce or Manipulate is fairly open-ended, but with room for the target to extract a promise of some kind first. Read a Person gives accurate information, drawn from a list of five possible questions (one of which is somewhat open-ended and feeds into Seduce or Manipulate pretty well). The thing is, PBTA punishes failure by making it the MC’s turn to use one of their moves, and that seems to be the source of everything getting worse. (Well, that and other players – AW embraces conflict between players.) The limited questions make sense in context as something you could read off of a person, but also provide some general limits.

A lot of individual playbooks also have moves to gather information off of others, PC or NPC. The Brainer is the obvious winner here, with powers like Deep Brain Scan, which opens up another list of questions to choose from. Such a scan requires “time and physical intimacy,” which is a pretty useful limitation even without hard numbers. You could just about call it an out-of-combat-only charm person, or suggestion but only as a ritual.

Apocalypse World also radically averts the issue of players not accepting the MC’s stakes and threats, because the MC doesn’t roll dice. Not to inflict Harm or anything else – the players roll all the dice. On 2d6, even with some bonuses, the players are eventually going to roll 6- results. Some nights, they will do this a lot. From there, the MC can do a lot of things, including inflicting Harm or making things get worse for one or more players Right Now, or announce future badness, or capture someone (PC or NPC), or… really whatever the MC feels fits the situation. AW characters just don’t build up the kind of resilience to Harm that D&D PCs can – and wouldn’t really want to, because recovering from Harm is a great source of experience.

Then there’s one little piece, a thousand times more important than anything else in the AW book, that is also true in D&D – but whole generations of players and GMs have forgotten it. I’ll just quote it here. (It is written in the first person, from the MC’s POV):

I’m not out to get you. If I were, you could just pack it in right now, right? I’d just be like “there’s an earthquake. You all take 10-harm and die. The end.” No, I’m here to find out what’s going to happen with all your cool, hot, fucking kick-ass characters. Same as you!

I have now meandered all over the place. I haven’t presented a solution, because I don’t know that there is one, beyond this: players should believe in the world, and probably also avoid playing characters that would engage in casual torture, unless everyone is on board with wallowing in the grimdarkness of it all. If you are heading in that direction, you owe it to yourself and the rest of the group to make sure you’re on the same page as to out-of-game-acceptable behavior. GMs and game-running committees, in turn, need to plan their plotlines around victories in many kinds of fights leading to the defeated NPCs yielding information to the players, while also planning the encounters so that the stakes aren’t “win, or everyone dies.” In general, I would recommend instructing those NPCs that will fold to do so while the threat of force remains implicit, or is restrained to threats. It’s okay to have some NPCs that won’t talk, but remember that when stymied, players will try to solve their problem in unconventional ways… so don’t stymie them excessively when it comes to gathering information from defeated enemies. Also remember that the players are always on the short end of the stick, when it comes to information – no one is truly trustworthy, no one is definitely telling the whole truth. Don’t dick them around without a really good reason.