5 Tips for Time Travel Stories

Quite a while back, a friend suggested that he’d like to see a post on how to run good time-travel stories in roleplaying games. I originally posted these in Harbinger of Doom – if not an exhaustive guide, then five pointers to make your time travel adventure manageable and fun. I’ve always loved the convoluted logic of these stories – Time Traveler’s Wife is one of my favorite books, and I enjoy Primer even though I’m not smart enough to grasp it without watching it a whole lot more.

First, a short list of assumptions.

- You’re not setting this game in the real world. Time travel stories in real world history are simultaneously a lot easier and a lot harder, just as games set in a facsimile of the real world are easier and harder (but more so).

- You’re not running a completely off-the-cuff game – you do some amount of session prep.

- Your rules of time travel permit change in the timeline based on the actions of the time-traveling protagonists, and those protagonists have free will in their own frame of reference. (Without this point, time travel is more like an extended vision than an adventure, and it lacks some of the fundamental what-if of time travel.)

- I’m not making any explicit assumptions about fate in the context of time travel. There are great stories where the PCs have apparent free will, but their actions in the past lead ineluctably to the present that they already recognized (perhaps caused by their greatest efforts to change that present). It’s the Anubis Gates and Time Traveler’s Wife model. It’s a lot easier to tell stories that don’t do this, though. Those can be amazing too.

Figuring out your cosmic laws and following them to their logical conclusion is the most important thing. You’re asking for a lot of suspension of disbelief from your players, so follow-through is crucial.

1. Limited Access

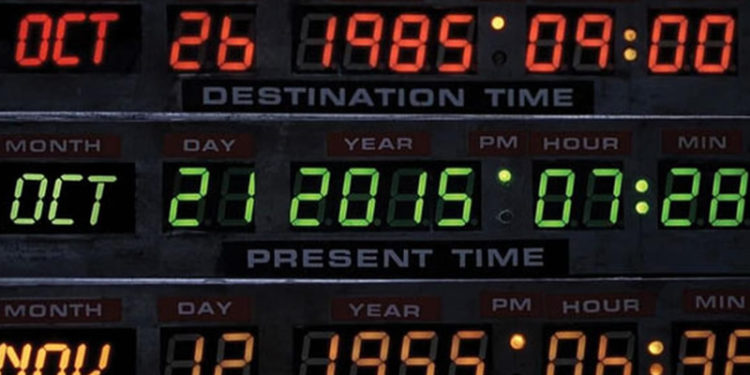

The first thing you can do to make your time-travel adventure vastly easier to tell is to sharply limit the number of trips your protagonists can make. Some time travel games, such as Timewatch and Continuum, are games entirely about time travel, as opposed to a time-travel adventure in a campaign that is otherwise not primarily about time travel, so it makes sense that they would reject this point. Even the Back to the Future series makes moving around in time inconvenient by requiring extraordinary amounts of energy and speed to trigger a jump.

What I think works best is a single time-travel venture, sending the protagonists to another point in time, with the understanding that they’ll either need to find someone in that time period who can send them home, or the phenomenon that sent them in the first place will snap them back into their own time at a particular point. The reason to do it this way is that you’re saving yourself a lot of questions around “why didn’t they just go back another year earlier and solve the problem a much easier way,” and the headache of retrying failed encounters or infinite prep time. (Again, there are wonderful games that do it the other way, but it’s baked into their system and all of their stories.)

2. Context is Key

Time travel stories reward knowledge as much as they provide it. This is the whole point of Lucy’s character on Timeless – she has the context of the people they meet when the other characters often don’t (which lets her also spout history for the audience’s benefit, obviously). A pure dungeon-bashing game, with minimal lore or recurring NPCs, probably doesn’t get a lot of benefit out of a time-travel story, because you’re just sending the characters to another time for which they also have little context. Look, Robert Zemeckis is a genius; the opening scene of Back to the Future is glorious exposition.

Establish a cast of characters in the PCs’ main timeframe. A few very-long-lived characters, such as intelligent undead, elves, treants, or a reincarnation open up a ton of story potential if you’re going into the past. Display how they’re the same and how they’ve changed. For example, in the Wildlands South second arc, we established an ultra-long-lived dwarf princess and her One Twoo Wuv, a revenant who repeatedly stomped into town and beat the snot out of the PCs. When the PCs went back in time, they got to meet the dwarf princess before everything went bad and her friendly, living human boyfriend.

This trick works basically the same if the PCs are going forward in time. I mean, obviously you get the Darkest Timeline whenever you go forward in time, because that creates the most tension. The only exception is when the campaign is at its end and you’re showing the PCs how their actions played out. Going forward in time, you should just about always find news headlines or a graveyard or something that reveals that you or a dear friend died tragically. I’m sure I don’t need to keep explaining Back to the Future to you, though.

The stronger of a central story you have connecting all of your important NPCs, the better. The ideal case involves NPCs in the present telling the PCs all about that one fateful day that everything changed, just before the PCs go back to roughly six hours before that day. The stronger and clearer that story, the more easily you can spin out likely consequences of PC interference in that situation.

3. Familiar Places

Just as important as familiar faces is a place the PCs know well. Back to the Future is again the lesson here, as the franchise shows us four iterations of Hill Valley. In fantasy, this might mean you jump from the time of the Good Kingdom back to the age of the Imperial Hegemony, so the local castle changes to a frontier outpost. Emphasize exploration by putting something interesting in the foundation of the outpost or on the grounds where the castle will someday stand. Also, never miss a chance to nod to Final Fantasy VI: have the PCs plant the acorn in the distant past that will someday become a mighty oak.

The physical terrain and everything built on and in (dungeons, y’all) are so important. Immortal beings aside, people are transitory; it is the land that remembers.

4. Mistaken Identity

This is another classic from Back to the Future. When your PCs arrive in the past or future, have them get mistaken for someone important. Most traditionally, you’d use their own ancestors or descendants, but in Wildlands South we emphasized the fish-out-of-water by having roguish characters get recognized as chivalrous heroes – the loyal armsmen of that revenant I mentioned.

The reason this is so great is that it draws those players into the action and uses the social pressure of expectation to keep them on their back foot. Follow all standard best practices about not discomforting players who find that anxiety-inducing. This is about surprise, altering personal context, and rapidly establishing relationships without having to chart the course to the relationship you want. Ideally, the PCs are under the customary Time Traveler Code of Silence, and have to go along with this to avoid revealing that they don’t know what the hell is going on.

Be forgiving, though, and have your NPCs obliquely coach PCs as to what is expected. There are two key techniques here – first, the “As you know, Bob” speech, where you rehash your plans. (Really fuck with the PCs by having the NPC ask them to deliver the recap. This is an advanced technique, so make sure your target is up for that kind of challenge.) Second, pin down as little as possible about the personality of the character you’ve “assigned” to the PC, so that you can shrug off numerous errors with an “oh, Todd, you’re such a kidder” and the like.

5. Fellow Travelers and Other Enigmas

There are plenty of interesting and fun time-travel stories you can tell that never involve the PCs leaving their present. Introduce logical breaks in causality and the known timeline that can’t be resolved with anything other than the action of a time traveler. I mean, the X-Men comics have told many stories that amount to “a stranger out of time,” usually a traveler from a possible future.

When you’re revealing the setting of the present day to your players, build in as many enigmas as possible. Think about ancient paintings that apparently show people alive today, characters or whole communities that disappear without a trace, and ancient objects that look new-made. Army uniforms or livery are especially popular for this.

When you’re halfway through the adventure and need a sudden twist, it’s hard to beat introducing another time traveler, either bailing the PCs out of a dead end or preparing their opponents with superior information. (Bad guys never follow the Time Traveler Code of Silence.) This is the fundamental premise of basically every Timeless episode, and it’s a formula that just. keeps. working. You should also use enemy time travelers to highlight the results of not caring about the consequences. (This is a specific case of “Villains are foils to the PCs.”) Another way to keep your PCs on their back foot: make them clean up the messes the NPCs leave behind, even if it’s just anachronistic knowledge.

Conclusion

These pointers are by no means exhaustive, and if there’s interest I might try for a second post on this topic. A few more great pieces of supporting fiction:

Night Watch by Terry Pratchett

Swiftly Tilting Planet by Madeline L’Engle (also Many Waters and An Acceptable Time, but Swiftly Tilting Planet is the easiest to borrow from for other stories)

Flight of the Navigator

Dragonlance Legends: Time of the Twins, War of the Twins, Test of the Twins

Looper

12 Monkeys

Donnie Darko

I’m… not the right person to explain how to mine the Terminator franchise for pointers to use it other time-travel stories. Especially as I’ve seen so little over the franchise as a whole.