Relative Moralism in Games

Before there was fire, there were Dragons. The fire brought heat, but those who did not possess it became cold. Life flourished, but so too did death become known. The mighty Lords rose up and found the strength to challenge the Dragons. Even with all of their Lordly might, they could the Stone Scales of Immortality remained upon the Dragons. Seath the Scaleless, angry and jealous, betrayed the Dragons who named him brother, and shared the secret of their defeat with the Lords. Thus the Dragons died, and the Lords stood tall. During this time, a child was born to a Dragon and an Other – human or goddess is unknown. This child was locked away from the world, feared by gods and man. This is the story of Crossbreed Priscilla – a case study of relative moralism in games.

Bearing My Souls

I’m a big fan of the Souls games – Demon’s Souls, Dark Souls, and Bloodborne (I’ve never played Shadow Tower, sorry!). I’m known to praise the sun. I take more than a passing interest in partying in Cainhurst. While I can – and do – talk about the storytelling and narration of the games at length, one of the points I frequently discuss is the way the games present morality to the player. (The only game that does almost a good a job as the Souls games in this regard is the first Dragon Age title, in my opinion.) Your actions only have context for you, and any people who happen to witness what you are doing. There are a few exceptions to this statement, but they are few and far between. For the most part, what happens in Anor Londo stays in Anor Londo. This puts even more weight on your actions – both in terms of what you do, and what you fail to do.

It’s time for me to share a secret with all of you. In all of my years gaming, the only time I have ever felt guilty about doing something in a game is when I played through Dark Souls and first encountered Crossbreed Priscilla. This might seem like a strange statement – I’ve been tabletopping for decades, and I’ve played a plethora of games with morality systems – but it’s the truth. I never felt bad about any of the stuff I did in Fallout 2. The absurd and humorous spin on even the most heinous act goes towards the hyperkinetic satire of the game – something lost in other Fallout titles outside of New Vegas. I even joke about the “bad decision knife/pistol” of the Dragon Age and Mass Effect franchises. Sure, you make “bad guy” decisions, but they don’t carry that much weight.

Relative Moralism in Games

Part of this is because the games with morality systems tends to reward your behavior. Even Dragon Age: Origins – which I love – does this. I despoiled the ashes of a saint. Instead of feeling bad, I was rewarded with a prestige class. Not to mention the fact it didn’t even impact my gameplay because my persuasion skills were so high. Mass Effect rewards your behavior by building your reputation, allowing your skills to be more effective and unlock additional skills. This system dates back to Knights of the Old Republic – another favorite – with very little deviation. It’s cool I can be good or bad, but I need to be both in different playthroughs in order to experience the full game. The narrative is starkly different based on my actions – even if the conclusions are stagnant. This speaks to replayability, but it also lessens that feeling of guilt or the weight of your actions. In order to experience the full game, you have to be an asshole. Since it’s not so much a moral choice as a systematic one, it blunts the impact.

In the Souls games, there isn’t a mechanical benefit to making bad decisions. You do receive tangible rewards, but the nature of the Souls franchise is such that tangible rewards often do nothing for you other than inform your subsequent playthroughs. If you are a sorcerer, that two-handed strength weapon isn’t doing shit for you, ya dig? The way the Souls games sell your decision-making is to have NPCs show up at the location you did stuff, and then perform their own actions. Sometimes this results in a fight, and sometimes it’s just to contextualize your actions. Importantly, the actions themselves occur in a vacuum. When you decide to kill someone, you are doing so because you want to kill them. The NPC will never respawn, and you might be left with a void that can’t be filled because of your desire to kill. Bloodborne breaks this mold a teensy bit, allowing you to visit an old god and resurrect some NPCs – because that’s better, right? (Spoiler: it’s not better.)

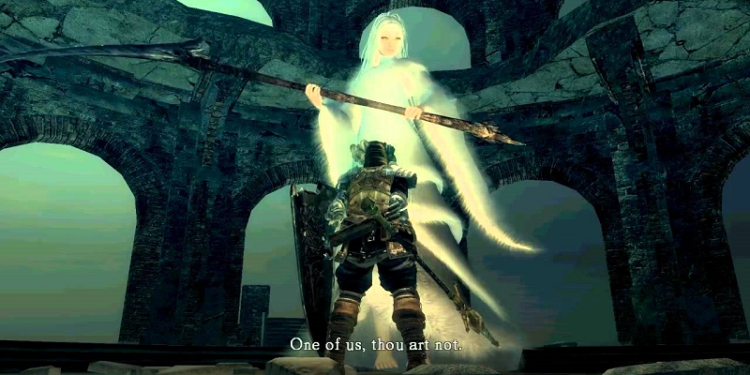

One of Us, Thou Art Not

This brings us to the story of Crossbreed Priscilla. I didn’t encounter her the first time I played through the game, as you can only access her via a special set of circumstances that is difficult to uncover on a first playthrough. She resides in an area called the Painted World of Ariamis, which you enter through a giant picture. The area is centered around a castle and church, with the underlying theme focusing on sins and punishment. One of the This is crucial to the story of Crossbreed Priscilla.

Through the snippets and environmental clues provided by the game, it is revealed that Priscilla is the child of a Dragon and some other being. She possesses white scales, making her visually similar to Seath the Scaleless – the only known albino Dragon. This is somewhat confirmed by the fact she is imprisoned rather than killed – signifying she is the child of a Dragon who is not killed, meaning Seath.

The identity of her mother is unknown, though the church in the area seems to be to the goddess Velka – including iconography depicting a mother and child marking the entrance to Crossbreed Priscilla’s area. Velka is the goddess of sin – punishing and pardoning in equal measure. Being Crossbreed Priscilla’s mother makes sense in light of her portfolio, but it might just be a situation where her acolytes are in the best position to watch over her. After all, her very existence is a sin. However, one of her special abilities speaks to the possibility that Velka is her mother – as well as providing one of the reasons for her to be imprisoned.

Guilt and Sadness

Priscilla – rather than being killed – is locked away in a secluded tower, guarded by a powerful knight, and locked behind a secret passage. Her life was spared, but she was deemed too powerful and too sinful to be allowed in the world. Priscilla possesses the power of Lifehunt – something even gods fear. Lifehunt causes stacking bleeding damage to targets it hits, while also causing the user to suffer cumulative bleeding – at a much lower rate. She’s also the absolute kindest person in the entire game.

When you encounter her, the exit to the Painted World is directly behind her. She asks you to leave her in peace, and continue on your way. By this point, you know her story, and there isn’t any indication she has done anything to deserve punishment other than existing. If you attempt to walk past her, you leave the level without a fight. If you fight and kill her, you do receive the ability to create a Lifehunt weapon, and you might even get a second Lifehunt weapon if you are pro during the fight itself. However, there is literally no reason to kill her other than loot. You can walk by her entirely, leaving her alive – alone and imprisoned, sure – but still alive. Her story is a sad one, and visiting violence upon her is even sadder.

Unjust Justifications

When I encountered her, I fought and killed her.

I didn’t want the weapon. There was no desire to get the experience or currency I would receive from her. I fought her because the rest of the Painted World was so angry and frustrated I wanted to leave nothing but a scarred wasteland behind me. I kept getting invaded by other players, having my brains pecked out by horrific bird people, and got rolled over – literally – by bonewheels. It was not my finest hour. In response, I vented my spleen upon poor Priscilla. After the fight, I read the items I received and instantly felt regret. Why did I kill her? I didn’t benefit at all. I took out my anger at her jailers on her. Does this make me a horrible person? It was – no joke- the worst I have felt about a decision I have made in a game.

Taking this moment, I pay it forward constantly in the tabletop games I run. To my surprise, it continues to pay off in spades. When presented with a situation to be bad people, the players will often take it – particularly if it is going to lead to further conflict. This is completely reasonable, especially when you take the above information into account. Players are becoming conditioned to expect bad decisions to just lead to more story – not necessarily introspection.

Tabletop Examples of Relative Moralism in Games

For example, my players framed someone for the theft of a religious icon and felt no remorse about it. They escorted a steel box that almost certainly contained some sort of intelligent being inside of it, and never felt the need to even look inside or get involved. This all speaks to the idea that these decisions lead to conflict and narrative progression. In these cases, they were not wrong. Continuing to support player decision-making is important, after all.

However, these same players witnessed a murder. It would have been easy for them to just walk away from this. No one saw them. There was no risk anything would have ever happened to them. Instead, the players felt so immediately guilty they didn’t stop the murder from happening – and at the idea the murderer would walk free – they barged into the house where the murder occurred, and got themselves into a very sticky situation. They also left a city in riots, burning, and in the control of a villain of their own creation. The first chance they had to help someone else – even though the person they were helping was an obvious scammer – they took it, because their guilt at the abandonment of the city was so tremendous. No one would have ever known it was their fault, but they knew it was their fault.

Making It Work

These are just two examples, but there are plenty I could choose from – across several games. In each case, the situations where only the players know what they did end up much more meaningful to the players. They have to wrestle with the decisions they made. The players have to live with what they did, their guilt weighing on them. The only narrative progression that occurs is character arc progression. The story changes only if the characters change. Moments like these give them the opportunity to do so. They have the chance to look at themselves through their actions and reflect.

More often than not, they don’t like what they see. For storytelling and character development, that’s a good thing. Providing options for relative moralism might result in less moral characters, but only in the short term – based on my admittedly small sample size, at least. In the long term, the characters will end up growing and changing. Isn’t that what it is all about?